Part of the Jim

Jarmusch ‘All About the Masters’ Series

* * ½

As I sit here writing this, Coffee and Cigarettes is quickly proving

to be one of the most difficult movies I’ve yet reviewed, so I apologize in

advance if this review is not up to my usual standard. To talk about this film as a whole is extremely challenging, as it makes more practical sense

to narrow it down from segment to segment (a handful of said segments were

originally released as short films, after all), but to do that would result in

writing the same overall thing over and over. In the grand scheme of things, Coffee and Cigarettes is one of those

films where the idea is better than the movie itself, but it’s still kind of

difficult to not be taken by its charming spell.

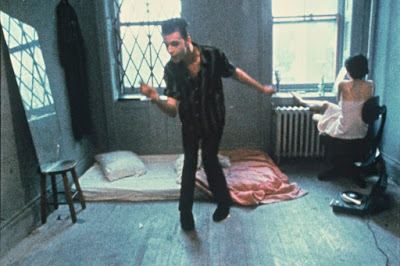

A series of vignettes

featuring conversations between characters with no connection whatsoever, and

the only mutual factor in each segment is that each dialogue is had over questionable

doses of coffee and cigarettes. In spite of the potential for witty writing and

quirky and unique characters (it does feature an impressive cast), the concept

(or gimmick, depending on your perspective) of Coffee and Cigarettes offers little to no promise of sprawling

production design, gorgeous cinematography, or a gripping plot. On one hand, it

is enough to make somebody laugh at a movie of such simplicity has the audacity

to exist. On another hand, it’s such a charming idea that you can’t help but be

drawn to it, even at the slightest level.

For us Jarmusch fans, it’s simply

mandatory viewing.

I suppose Coffee and Cigarettes exhibits the levels of quality Jarmusch is

capable of, from his absolute worst to his absolute best. There are some

moments are just there with nothing particularly remarkable to say about them,

and the most you can say has already been said by the title. One particular segment,

“Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil” (featuring notable rock due the White Stripes),

is insufferable in just how hard its trying to be so quirky and indie.

There are some segments that have

something very interesting going on, no matter how little is happening. Take,

for instance, “Renee”: a lovely young woman sits by herself reading “Guns N’

Ammo” while the young waiter repeatedly visits, desperate to start a

conversation. Though that’s the entire scene, I sense something going on in the

undercurrents, and the result is very alluring. Unfortunately, though, the

scene cuts too short. There are a number of segments that meet a similar fate.

And then there’s a number of

scenes that are just there that I simply cannot comment on if my life depended

on it, like “No Problem” and “Cousins” – in spite of some great talent present,

there is absolutely no substance whatsoever (with the exception of the latter’s

ending). But then there are some moments that truly shine. Two in particular

come to mind – “Delirium”, where the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA and GZA find themselves

being waited on by the one and only Bill Murray (all playing themselves, by the

way). The other most notable segment is “Somewhere in California”, featuring Tom

Waits and Iggy Pop extolling coffee and cigarettes as the perfect combination.

The latter segment was once released as a short film, and actually won the Best

Short award at the Cannes Film Festival.

As for the overall product: while

none of the actors present really exhibit their abilities, their mere presence

does bring some excitement, I must admit – how can you not love a conversation

between Roberto Benigni and Steven Wright, even if there’s practically nothing to

the scene itself? Scenes don't really transition, nor is there any individual identity to the segments, but Jarmusch does captures the very activity of coffee and cigarettes

extremely well (and, yes, I am considering that an activity unto itself), with the

gritty photography and various cafes utilized. Ultimately, Coffee and Cigarettes is probably more sizzle vs. steak, but it

needs to be seen to be believed.